A Brief Perspective of ICT

ICT and History

The Global SoS Network promotes ICT as the most practical and modern means for bringing about productivity-driven sustainable societies. But ICT is not just the Internet and computerized office equipment, devices, and gadgetry.

In a literal sense, Information and Communications Technology refers to technology as used to communicate information. This does not necessarily involve computers, or even electrical or electronic signals of any type. Thus, the broader meaning of ICT refers to methods human society has developed in order to satisfy the need to communicate through long distances, just as technology like the making of fire or the use of the wheel satisfies needs for portable heat sources, or for transportation at great distances.

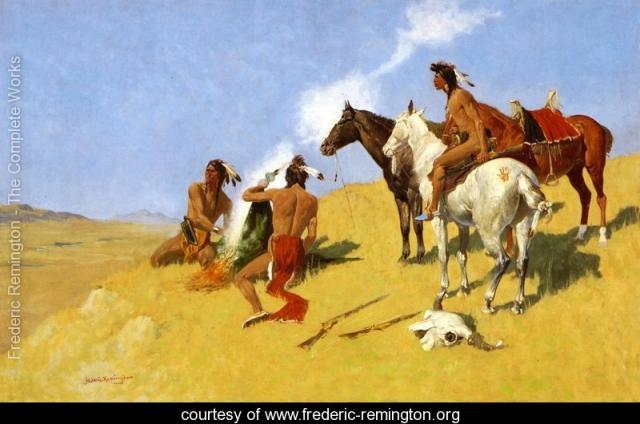

In that context, drum telegraphy in Africa was a good example of the use of ICT. It was a long-distance method -a technology- for sending and receiving information. So were the smoke signals used by Native Americans centuries ago.

An interesting and revealing fact is that both drum telegraph and smoke signals employed discrete yes-no signalling sequences. Although they were not electronic, drum telegraph and smoke signal communication are part of the digital ICT tradition.

Soldiers stationed along the Great Wall of China employed ICT when they relayed information with fire-lit devices. Their method represented the level of technical progress avaliable as a communication tool against invasion.

ICT were used by the ancient Greeks when they ran with written papyrus to relay news, for example, from the battlefields to the rulers. It was an adequate technology for the era. Existing know-how provided information by means of written communication between battlefield commanders and the rulers of the realm.

Wikipedia informs that as early as 3000 years ago, carrier pigeons were used to proclaim the winner of the Olympics. More recently, semaphore and then electrical telegraphs plus postal services, along with typewriters, were the mainstay of ICT. Postal services have proved to be the more durable Information and Communication Technology, now joined by telephones, computers and the Internet -which itself originated from war-game scenarios.

ICT and the Future: How to Forge Swords into Ploughshares

It cannot be stressed enough that democracy should not be seen as some distant entity to be influenced by technology. As a sociotechnical system of systems, that is, a system made up of other smaller systems, it might be best to see democracy as the technology -the method- human society employs to govern itself. As such, it is or should be seen as a routine collaborative task: A simple, convenient, economic and very rewarding task.

As ICT evolves at the beginning of the 21st. Century, humanity is reaping great benefits from the acceleration that the ICT field is undergoing. Innovations that are reaching the marketplace, such as...

...are creating social forces that push back technological constraints. ICT simplifes the tasks every human must carry out when stress makes him or her feel that improvements must be made in the socioeconomic, or natural environment.

The practical usefulness of ICT will reveal that a lot of the monies being used for development aid will not be needed in order to achieve desired results. This means that instead of expecting to have to give increasing amounts of international aid for reaching stated goals in the international development area, such as the 17 SDGs, donor nations can look forward to meeting or exceeding stated goals, with diminishing budgets for donations and foreign aid to emerging nations.

Additionally, with the use of ICT for the systematic resolution of conflict, all social groups will employ their legislative Systems of Systems in order to accomodate themselves to each other, and so will nations. Eventually, legislators the world over will focus on increased productivity as their primary concern. Nations will enter a new era where the common goal will be the improvement of sustainable productivity. The new era will mark the ending the application of scientific resources for the settlement of conflict through warfare and destruction, thus eventually there will be no further need for standing armies.

Very importantly, the mass media keeps constituents updated in regards to the overall economic, social and natural environment, making the media essential components of legislative Systems of Systems.

Therefore, whenever legislative systems operate properly, constituents will rely on the media in order to contemplate the effect of human activities on the environment. The media help constituents take into account resource limitation. The media will facilitate the process through which constituents will regulate growth and reformulate sustainable productivity expectations by taking into account the ultimate constraints posed by global environmental protection.

Checking the Facts

All this may sound idealistic. But pause must be given for visualizing the technical progress humanity has achieved through the 5 millennia between the time maybe only kings were able to muster resources to use ICT artefacts like the Rosetta stone, and today. Notwithstanding the digital divide, at the beginning of the 21st. Century, virtually any determined enough human can employ the same raw material -silicone- and communicate information to practically anyone else on the planet. However, perhaps a recent-history example may help give a clearer idea of the generative power that ICT-enabled constituent-legislator dialogue can accumulate, and then unleash.

Breaking Logistical and Technological Constraints

The typical design for Parliamentary Outreach Mobile Training Units (MTUs), usually equipped with computers, has a very high publicity value. MTUs can transport mobile post offices to help impress the importance that effective utility and tax billing systems have for the creation of wealth, and for creating income streams for financing the daily operational costs of the Machinery of Government. MTUs can also transport scribes so that even illiterate and other disadvantaged constituents can learn how to contact their legislators, thereby meeting the information needs of their democratic system. Image: © UNDP

As a global steward, the Global SoS Network will promote information regarding the availability of resources for initiating environmentally-friendly processes that will establish systematic resolution of conflict, unravel industrial underdevelopment, and eradicate Global Poverty. And the resources are impressive.

According to the Universal Postal Union (UPU), there are around 700 thousand post offices in the world. Most of them are located in the developing world, and most are underused. Even more impressive is the exploding ICT capacity the world is experiencing. But, how would it all work?

|

How can people and computers be connected so that -collectively- they can act more intelligently than any individuals, groups, or computers have ever done before?

MIT Center for Collective Intelligence

|

"In most countries the entire population has access to postal service. This is not yet the case for many modern forms of communication such as fax and electronic mail." These are the words of Thomas E. Leavey, Director General of the Universal Postal Union, in the editorial "Letter from the Director General," of the UPU’s 1997 Annual Report. Mr. Leavey was also an Assistant Postmaster General for International Affairs of the United States Postal Service.

Notwithstanding Mr Leavey´s statement, the fact that a determined geographical area is serviced by a post office does not mean that the post office offers adequate postal service. So the fact that a country´s population has access to postal services does not mean that they do receive mail at home.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation gives the following results if, say, 4 billion humans are to establish communication with their legislators. In the first instance, it might take an average of 4 letters or emails to their legislators per year to solve, say, the Global Poverty problem.

If half of those documents are posted, that is at least 8 billion messages that legislators must respond to by post every year.How many post offices or email centres are required for that volume? Although they are basing themselves on other requirements, REMCU has established a useful yardstick: a ratio of one radio email system installed per 4,000 humans.

A few decades ago the UPU estimated that adequate postal services required around one mailbox or post office per 25,000 inhabitants. So for the sake of constituent-legislator dialogue, the existence of an ICT facility per around 10 or 14 thousand constituents could probably help make the difference beween the present environmental and social situation, and the initiation of constituent-conflict resolving dialogues all over the world. Calculation of 4 billion poor humans being served by, say, 400 thousand post offices, gives a ratio of a post office per 10 thousand humans. It is presumably a good start.

It is hard to beat the allure of interactive websites and the convenience of instant communication that electronic mail offers. The attractiveness of electronic communication, especially with the aid of AI-enabled communication, might just what constituents need in order to grasp relevant issues and establish effective and efficient dialogue with their legislators, and to get prompt replies. Does e-mail represent the fast and new, and do postal services portray the slow and old? By no means. Postal services provide a method to send formally undersigned documents that could be required for public or formal matters. A good thing that could be said for both teledemocratic techniques is that the low price and institutional presence and formality of postal services tend to complement the speed and flexibility of the Internet.

In an address to the Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), in Brussels, May 2001, Mr. Leavey indicated that out of 440 billion items posted in 1999, more than 80% were posted in industrialized countries, which made up less than 15% of the world's population. Accesing a post office or a mailbox in those countries is, at least, relatively convenient.

Mr. Leavey also said that less than 20% of the aforementioned items were posted in developing countries, representing more than 85% of the people in the world. How many post offices are within convenient walking distance in the developing world? More importantly, can developing-nation constituents trust that their mail, or the reply from their legislators, will be delivered at all? E-mail bypasses those concerns, which leads to the premise that the Internet could always be an effective spearhead.

There is clearly room for growth here that can be attained with judicious installation and improvement of teledemocratic infrastructures, well-thought-out employment of scribes in nations with high levels of illiteracy, and sensible training for emerging-world constituents in the art of writing meaningful and efective letters -or email messages- to legislators. These activities will help assure that whenever constituents in the developing South want to establish dialogues with their legislators, they will feel comfortable by doing it through the convenient teledemocratic infrastructure of their nation.

|